A very complex geology

Limestone and dolomite to the west

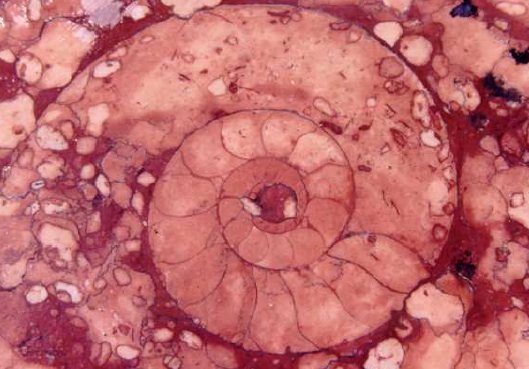

In the western Queyras, sedimentary rocks (limestones such as the pink marbles of Guillestre , which contain beautiful ammonites, dolomites, marls, sandstones) have undergone the effects of the uplift of the Alps in the recent geological past, with its folding, thrust sheets and stacking of sheets.

Limestone and dolomite are clearly visible at Ceillac, where they formed the Font sancte and the montagne d'Assan, and at Arvieux, at the pic de Rochebrune. They form majestic cliffs that are difficult to cross (Combe and Gorges du Guil), and are at the origin of Queyras ' isolation from the rest of the Hautes Alpes department, and of Ceillac's historic separation from the rest of present-day Queyras

Dolomite and cargneule

Limestone is a calcium carbonate, while dolomite is a double carbonate of calcium and magnesium, which is much less soluble (on a geological scale) than limestone.

Dolomite has formed imposing cliffs and peaks such as Font Sancte in Ceillac, as well as the ruiniform landscapes of Nîmes le Vieux and Montpelliers le Vieux on the Causses.

When limestone and dolomite were deposited together, at the bottom of a lagoon for example, the more rapid dissolution (on a geological scale) of the dolomite by gypsum water formed the cargneules, the vacuolar-looking rocks that can be seen at Casse déserte.

Lustrous shale in the center

In the center, metamorphic rocks dominate, notably schists, which are clays "baked" at great depths, causing them to lose all trace of fossils and previous folding. Some of these schists have been cut into roofing slates.

Folded shales could only have formed at high temperatures (400 to 500°C) and under high pressure, at great depths (3,000 m and beyond). The plastic rock was able to bend without breaking.

The glossy schistres, softer than the limestones, have not preserved the traces of the glaciers and have given rise to the more open valleys that can be seen at the end of the Combe du Guil, such as the Arvieux valley or those located upstream of Fort Queyras(from Château-Ville-Vielle to Ristolas via Aiguilles-en-Queyras and Abriès), or at Molines-en-Queyras and Saint-Véran. Geology is thus at the origin of the Queyras' unity, its geography and later its historical unity.

Basalt and gabros to the east

To the east, crystalline "green rocks" such as ophiolytes, gabros, serpentines and basalts can be seen on the summits of Abriès(Bric Bouchet) and Saint Véran(Mont Viso)

Fine samples of green sepentine can be found in the Guil pebbles at Ristolas.

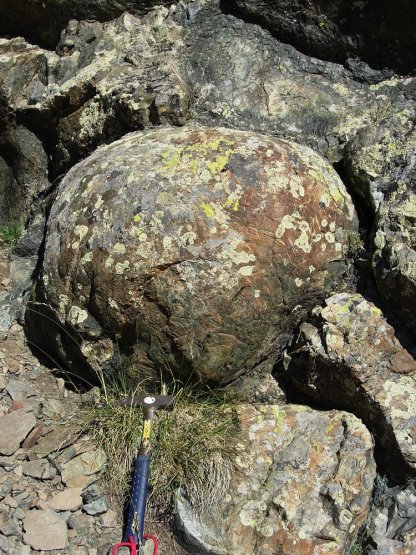

Pillow basalts

They formed at the bottom of deep seas (around 3,000 m) during volcanic eruptions. The molten lava formed a crust on contact with the water, taking on the shape of a balloon that was eventually torn apart by the pressure inside, creating a new cushion.

At Chenaillet and Colle Verde near Montgenèvre (Hautes Alpes), these cushions are particularly abundant. A great walk from Cervières for anyone interested in geology.

They can also be seen at the Tête des Toilies above Saint-Véran.

Among the sedimentary rocks are gypsum and cargneous rocks, formed at the bottom of a lagoon and which have produced the remarkable landscape of Casse Déserte in Arvieux, on the road to the Col d'Izoard, with its towers, minarets, stone lacework... all these dissolution funnels and the remarkable Ruine Blanche ravine in Montbardon (Château-Ville-Vieille).

Geology is responsible for these very special landscapes.